What is Osteoporosis and why does it matter?

Osteoporosis means porous bones in Greek and has been defined as

‘A metabolic bone disease characterised by low bone mass and micro architectural deterioration of bone tissue, leading to enhanced bone fragility and a consequent increase in fracture risk’

It is the deterioration in bone tissue or bone mineral density which contributes to bones becoming fragile and this fragility increases the risk of fracture. This is why Osteoporosis is so important. Unfortunately we do not experience any symptoms of bone loss. The first sign of a problem can be a fracture usually caused by low trauma or no trauma at all. A fracture is the same as a broken bone.

What do bones do?

Our bones are important throughout our lives and are a living tissue being renewed and replaced all the time, just like our skin. This is continuous from when we are born until we die.

Bones support our bodies and allow us to remain upright, attach tendons and ligaments which work with muscles allowing movement, protect our organs and store minerals such as Calcium, protect our vital organs such as brain, heart and lungs etc, and help make blood cells to assist our immune systems and move oxygen around the body for other cells and organs. Different types of cells continually make (osteoblasts) and remove bone (osteoclasts) in a process called bone turnover or remodelling. Bones are made up of collagen or protein, along with minerals, such as Calcium.

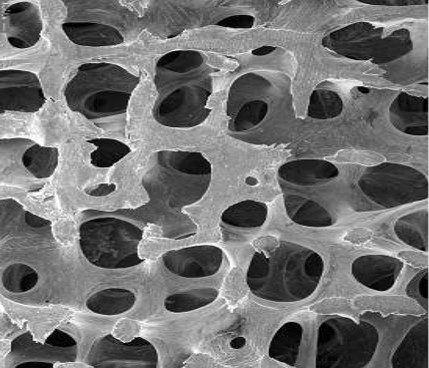

There are two types of bone. The outer bone surface is called cortical or compact bone. The inner meshwork is called cancellous, trabecular or spongy bone and is made up of a rigid meshwork which gives our bones maximum strength for minimum weight. The amount of the two types of bone varies depending on the particular bone site.

Bone Structure

Cortical / Compact

Cortical / Compact- 80% Skeletal Bone

- Surfaces of all bone

- Majority in shafts of long bones

- Peak formation 20-24 years

Cancellous / Trabecular

Cross Section of

- 20% skeletal bone

- Rigid meshwork - maximum strength for minimum weight

- Majority of a vertebral body and end of long bones

- Peak formation 12-16 years

Cross section of Proximal end of Femur

© reproduced with permission of FAB Project University of Glasgow

| Healthy Bone | Osteoporotic Bone |

|

|

|

© Tim Arnett, University College London (t.arnett@ucl.ac.uk) |

|

When bone is magnified you can see the rigid meshwork with healthy bone having a strong meshwork which gives maximum strength for minimum weight. The osteoporotic bone shows the meshwork that has become fragile and much more likely to fracture. Both the end of the wrist, hip and the spinal bones, called vertebra, are rich in this trabecular, spongy or mesh like bone and when the mesh becomes fragile the bones are more at risk of fracturing or breaking. Therefore, common fracture sites for osteoporotic fracture are the wrist, vertebra and hip.

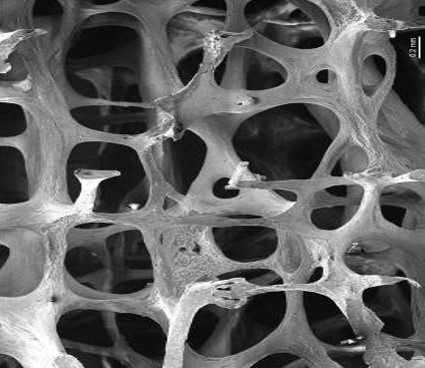

Lifetime changes in bone mass

Bone is built rapidly in childhood, especially during adolescence. Men tend to have slightly higher bone mass or density than women. Both sexes reach the maximum amount of bone by their late twenties and reach what is known as Peak Bone Mass. This is the most amount of bone we will have during our lives. The amount tends to plateau and remain constant until our 40’s and then bone loss starts to occur naturally. After this we normally start to lose bone as a part of aging. Men lose bone at a fairly constant rate of approx 1% a year. However, women experience the menopause and lose the protective effects of oestrogen and this causes the bone loss to accelerate to approx 5% a year post menopause. So, whilst osteoporosis is more common in post menopausal women, it can also occur in men.

However, in certain circumstances it can also affect children, younger women and also pregnant women but this is far less common.

Bone formation and loss

Bone is a living tissue constantly being made and removed by special bone cells in a process called formation, these cells are called osteoblasts, and resorption, these cells are called osteoclasts. This process is called bone turnover or remodelling and continues throughout our lives and an adult skeleton is renewed every 7-10 years. As already explained, our bone mass or density changes throughout our lives and bone loss occurs naturally as we age which can lead to osteoporosis and an increased risk of fracture. A DXA scan can determine the bone mineral density or BMD and determine a diagnosis of Osteoporosis and may also help assess the risk of fracture or broken bone.

Who does Osteoporosis affect?

We do not feel bone loss. It is completely asymptomatic and the first sign that things are not right MAY be a fracture. Osteoporosis does not cause pain but fractures do.

Our bones should be strong enough to support us if we have a fall from a sitting or standing height and if a fracture occurs under these circumstances it is known as a fragility or low trauma fracture. Sometimes these fractures occur without excessive trauma, especially in the spine.

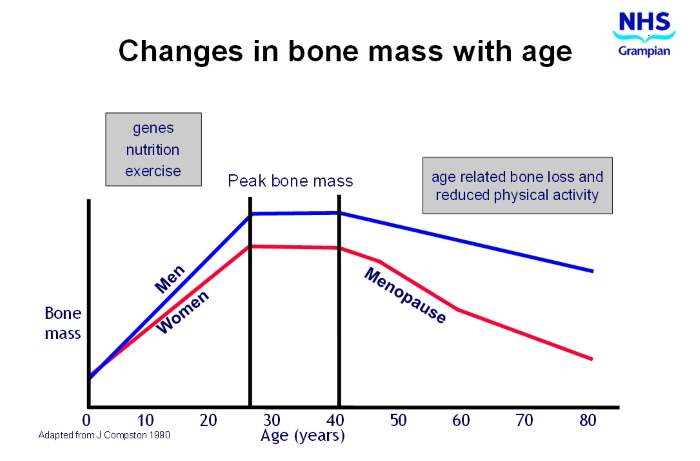

In the UK, it is estimated that the lifetime risk of sustaining a fracture from the age of 50 is 1 in 2 women and 1 in 5 men – many of these as a result of poor bone health and low bone density.

The lifetime risk for women of fracture at age 50 is greater than the risk of breast cancer or cardiovascular disease and the lifetime risk for men of having an osteoporotic fracture is similar to developing prostate cancer.

However, Osteoporosis can also affect children, younger women and also pregnant women but this is far less common.

Definition of Osteoporosis

In 1994 The World Health Organisation defined the diagnosis of OP based on the DXA Bone Mass Density results based on Standard Deviation comparison of the value with young adult mean figures. See Table 1

However, whilst these figures are valuable it is very important to understand that it is the overall fracture risk of an individual that is the most important assessment when considering who may require treatment and at what time point therapy this is required to reduce that fracture risk.

Table 1

WHO Criteria for Diagnosis of Osteoporosis in Postmenopausal Women 1994

| T-score | Osteoporosis Definition |

| T score -1 | Normal BMD |

| T score -1 to < -2.5 | Borderline osteopenia or low bone mass |

| T score < -2.5 | Osteoporosis |

| T score < -2.5 + fragility fracture | Established Osteoporosis |

Who is at risk of Osteoporosis?

Osteoporosis is more common with age and females are at greater risk especially after the menopause when the loss of oestrogen speeds up bone loss.

A low bone mass or BMD identified by a DXA scan is one known factors that may increase fracture risk and we also know that certain factors contribute to low bone mass and increased fracture risk. Research has shown that SOME of these increase the risk of fracture independently of a low BMD.

Female - Early menopause before the age of 45years or hysterectomy with ovary removal

Genetics – a parental history of a hip fracture or of Osteoporosis increases your risk

Ethnicity – those who are Afro Caribbean are at lower risk than Caucasian or Asian origin

Low Body Weight - BMI of 20, compared with a BMI of 25, was associated with a nearly twofold increase in relative risk for hip fracture

Alcohol Excess

Smoking

Immobility and lack of physical activity especially weight bearing exercise

Medical conditions:

- Inflammatory Rheumatic Disorders (e.g Rheumatoid Arthritis and Systemic Lupus Erythematosus)

- Inflammatory Bowel Disease and Malabsorption (Coeliac Disease, Cystic Fibrosis) where food absorption may be reduced

- Conditions that affect some Hormone levels. These include high levels of Thyroxine and Parathyroid Hormone and also the sex hormones caused by an early menopause (before the age of 45 years in women) or conditions such as anorexia nervosa, prolonged episodes of no periods (Amenorrhoea) and genetic conditions such as Turner’s syndrome or).

In men conditions that cause low testosterone levels which may also increase the fracture risk.

- Other conditions include Diabetes, HIV, Chronic Liver disease, Chronic Asthma, Renal Disease and organ transplants.

- Some cancers such as myeloma

- Neurological conditions and those that may cause prolonged Immobility and a sedentary lifestyle: Stroke, Parkinsonism/ Multiple Sclerosis/ Alzheimer’s.

Certain medications

- Glucocorticosteroids(e.g. Prednisolone >2.5mgs for >3 months)

- Aromatase Inhibitors (breast cancer treatment)

- Gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) inhibitors

- Anti androgen therapies or Androgen Deprivation therapy ( ADT)

- Anticonvulsants

- Antipsychotics

- Depo-Provera (a contraceptive medication)

- Long term anti depressants

- Proton Pump Inhibitors e.g Omeprazole

- Thiazolidinediones (particular type of diabetic drug)

How is it diagnosed?

A DXA scan is the most reliable, reproducible and accurate method to assess bone mineral density or BMD and this scan can help assess your future risk of fracture.

It also helps identify those who have osteoporosis and those who will benefit from treatment. If your risk of fracture is high then you will be recommended to commence a bone treatment to help reduce this fracture risk.

Fracture risk assessment

Bone mineral density which is assessed by a DXA scan forms part of a Fracture risk assessment and both the need for DXA scan and any subsequent recommendation for treatment.

The Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) develops evidence based clinical practice guidelines for the National Health Service (NHS) in Scotland. SIGN guidelines are derived from a systematic review of the scientific literature and are designed as a vehicle for accelerating the translation of new knowledge into action to meet our aim of reducing variations in practice, and improving patient-important outcomes.

Latest guidance

As we have seen there are other known risk factors that contribute to fracture risk over independent to BMD. Tools have been developed to allow individual information regarding these risk factors to be entered and this then calculates an absolute percentage fracture risk over a 10 year period. In Grampian, we have defined criteria based on these risks and percentages that generally determine whether you are eligible for a DXA scan and also whether you require any subsequent treatment. Certain circumstances mean you do not have to have a FRAX undertaken.

FRAX risk assessment tool

Fracture Risk Assessment Tool (FRAX) is used widely and is available in country specific and different formats. It can be accessed on the internet.

FRAX can be reached by following this link and selecting relevant country: www.sheffield.ac.uk/FRAX/

This shows the calculation tool. The information required is age, height and weight, fracture history, family history of hip fracture, steroid use, alcohol and smoking habits and whether they suffer from other conditions such as Rheumatoid arthritis (see site for more information via link above).

Will I require treatment?

A diagnosis of osteoporosis does not automatically mean you will break a bone or another one if you have already done this. Neither does it automatically mean that you will require bone medication. A diagnosis of Osteoporosis may increase the future risk of fracture depending on an individual’s medical history and particular circumstances and risk factors.

The DXA scan assessment forms PART of a fracture risk assessment for an individual.

Any recommendations for treatment and/or rescan will be made on the DXA report along with if your GP should undertake some simple blood tests to exclude possible medical conditions. It may be recommended that you have another DXA scan in the future to assess your risk at that time point if treatment is not currently recommended.

Only those at a high risk of fracture are recommended to receive bone treatment. This is usually for 5 years with further DXA reassessment after this. Your GP will generally need to refer you to the service for a repeat DXA.

If you have a fracture whilst on treatment then it is important that you discuss this with your GP as we may wish to undertake a further DXA to ensure everything is progressing as it should.

What about if treatment is recommended?

Any recommendations for treatment and/or rescan will be made on the DXA report along with if your GP should undertake some simple blood tests to exclude possible medical conditions.

If recommended to have treatment for bone health it is important to start this, take it correctly and as instructed and to continue it on a long term basis. These treatments are effective at reducing the risk of fracture even though changes in the bone density may not be seen for many months and you may not feel different on it.

Most importantly, if you experience any problems you should seek help and advice immediately from your GP as alternative treatment may be available.

Stopping recommended treatment without a suitable alternative will usually increase your future risk of fracture.

Further information on treatments is available.

What about lifestyle changes?

There are a number of things we can all be aware of and try to do to maintain the health of our bones. This applies whether we have Osteoporosis or not.

See Looking after your Bones.

Further information and patient resources

The Royal Osteoporosis Society - The UK’s only national charity dedicated to bone health and osteoporosis.

Visit: theros.org.uk

Call: 0800 80 0035

E-mail nurses@theros.org.uk

Published: 19/05/2022 11:44